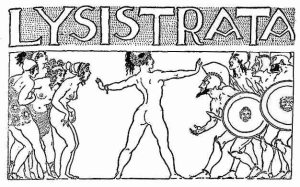

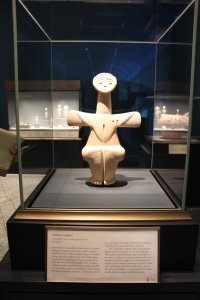

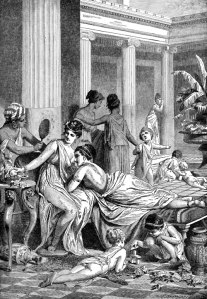

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?” This is the question Faustus asks upon seeing Helen enter in Act 5, Scene 1 of Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. It is true that mythology tells us of the female power (both mortal and immortal) to condemn empires to ruin and birth new ones into existence. The beauty of Helen (and the lust of Paris) ignited the Trojan War, the beauty of Rhea Silvia (and the lust of Mars) birthed Romulus and Remus, and the beauty of Lucretia (and the lust of Tarquinius) ignited the fall of the Roman monarchy. Pandora, the first woman made in the image of an immortal man, brought forth the evils of the world by virtue of naïve curiosity. One of the first primordial deities, Gaia (ostensibly female), birthed the natural world. Why is it then that women who appear to play so central a role in the stories of antiquity were subject to subordination by men? Were these females forever doomed to brighten the pages of Homer, Hesiod, Livy, Ovid, and Vergil as mere beautiful mutes, whose physical violations propelled stories not their own? Or perhaps as jealous goddesses constantly out to exact revenge on any who pose a threat to their beauty? Were those who spoke out against the cruelties and infidelities of men fated to be deemed maniacal she-devils? The name Medea, even today, conjures images of a foreign madwoman. We remember her for her atrocious crime of filicide. But what of her husband Jason? He used Medea to get what he wanted and tossed her to the side once she got in his way of acquiring more fame and fortune. Medusa, the most famous Gorgon, is remembered for her head full of snakes and ability to turn all those who gaze upon her to stone. Although there is debate as to her origins, Ovid posits that she was initially a beautiful maiden who was raped by Poseidon. Athena, enraged, transformed her into a monster. Men call these women crazy – most contemporary women follow suit.

Among the male writers of antiquity who wrote about women, there is one in particular who appears unique. Apuleius was a Numidian Berber from Madauros who purportedly lived from 125 -180 CE. Apuleius received his education in Carthage and Athens. After a somewhat scandalous marriage to a wealthy widow, whom he was accused of using magic to seduce, he retired to Carthage were he held the chief priesthood of the province. The contemporary world knows him best for his most famous work The Golden Ass, which is written in Latin. While the story is centered on Lucius and the metamorphosis of men’s shapes and fortunes, it is propelled by the stories of women. Lucius becomes a plaything of Fortune – anthropomorphically feminine. In a twist of fate, the voice of the author fades into that of the narrator and is controlled by the events of the story, which (as author) he had purported to control. Upon losing control, the females of the story rule his fate. In the following paragraphs I will examine the different types of women that Apuleius writes about and the uniqueness of their voices. I will then draw a parallel to representations of women in post-modern America.

There are a slew of powerful, “evil” women that cause quite a commotion in The Golden Ass. Many are demonized for their witchcraft or licentious behavior. How curious that an adulterous man is considered unable to control his lust and therefore doing nothing outside of his nature, while an adulterous women is being savagely immoral! Lucius comes upon Aristomenes who tells him the story of his involvement with a powerful woman named Meroe who sought vengeance upon her lover, Socrates. Aristomenes describes how Meroe retaliated when the indignant townspeople agreed upon stoning her to death: “However, she thwarted this move by the strength of her spells – just like the famous Medea when, having obtained a single day’s grace from Creon, she used it to burn up the old king’s palace, his daughter, and himself, with the crown of fire. Just so Meroe sacrificed into a trench to the powers of darkness…” (12). Here, Meroe is likened to Medea: both women evil in their ways. She goes on to cut Socrates’ throat, pee on Aristomenes, fool them into thinking the violence of the night before never happened, and finally reveal that she did indeed cut Socrates’ throat, causing Aristomenes to flee to exile. While Meroe’s actions appear rash, it is an interesting role reversal. In this sequence, the women are in power and the men are powerless. This is not a common occurrence in antiquity, especially among mortals. Also, early on in the segment, Aristomenes comments on Socrates’ haggard state in an unusual manner: “You deserve anything you get and worse than that, for preferring the pleasure of a leathery old hag to your home and children” (11). Despite his use of derogatory jargon, Aristomenes is calling Socrates out on his infidelity, placing the blame on him rather than the woman. This is a rarity.

As Lucius’ journey continues, he encounters Byrrhena, the woman who raised him. Byrrhena is a strong female character. She rules over her household and seems to be lacking neither in disposition or circumstance. She warns Lucius to, “Watch out for the wicked wiles and criminal enticements of that woman Pamphile, the one that’s married to Milo, him you call your host” (24). However, it is Lucius who reveals himself to be lacking in character, as he is obsessed with magic and refuses to heed the words of advice from Byrrhena. The fool will become an ass. But first, he diverts his attentions to Photis, Pamphile’s maid, whom he says he’ll “have a go at” (25). To him, she is merely an object – the object of his desire. His behavior is voyeuristic as he watches her sway her hips while she cooks. He comments about her hair, suggesting that, “it’s only a woman’s head and her hair that I’m really interested in” (26). By objectifying her, he succeeds only in making himself look like a fool. He is so desirous of her body that he can barely contain himself, while Photis remains collective and tells Lucius to keep calm. How interesting that women are often depicted as the irrational ones!

Book 2 of The Golden Ass finishes with a story given by the disfigured Thelyphron at Byrrhena’s dinner party. Thelyphron tells of the evil women who steal body parts to conduct spells. Thus, every corpse must be carefully guarded in the night. Thelyphorn is enlisted to guard a prominent dead man for the evening, but ends up getting his nose and ears cut off by the witches who mistake him for the man. Here again, the women have the upper hand. Even the man who has died insists his death was at the hands of his adulterous wife. The men appear helpless, even foolish, in the face of these women. The consequence for Lucius’ own foolishness rears its head once he insists that Photis help turn him into a bird like Pamphile. As she does so, his persona is amplified by his unexpected metamorphosis into an ass, thus beginning the succession of unfortunate events that befall him.

Shortly after his transformation, Lucius is robbed and taken to the robbers’ stronghold. Not long after he arrives, a kidnapped girl of noble birth named Charite is also brought to the stronghold. The robbers remark about the profit the girl will bring them – another woman as object. The old woman who takes care of the robbers (old women in this story are not respected for their age but are instead disdained for their haggard appearance) tries to comfort the young girl by telling her the story of Cupid and Psyche. Though I will not relay the entire story, it is unique in that the protagonist is a strong female who endures and overcomes trials and tribulations much like Hercules and Odysseus. Psyche is punished for her beauty by her evil sisters and the jealous tyranny of Venus. Her naïveté and curiosity get her into even more trouble, much like Lucius. Apuleius seems to parallel the two stories throughout the book: of the misfortunes of Lucius and the misfortunes of Psyche. However, it appears to me that Lucius escapes his misfortunes out of sheer luck. Though Psyche is aided in her various trials by those who take pity on her, it is her love for Cupid that enables her to endure; exacting revenge on her sisters and escaping the brutality of Venus. In the end, she is not raped or killed, but is rewarded for her bravery with immortality.

As Lucius’ own story continues, Charite’s lover comes to rescue her in disguise. By this time Charite has proven herself a strong-willed individual, despite her initial bouts of weeping, when she attempted to flee her captures on Lucius’ back. Before Lucius is aware of Charite’s relationship with the new addition to the crew of robbers, he is all to quick to pass judgment on her behavior: “That, I felt, justified me in condemning the entire female sex, when I saw this girl who had pretended to be in love with her betrothed and to be pining for a chaste marriage, now suddenly delighted by the mention of filthy sordid brothel” (117). Who was there to pass judgment on Lucius when he had his way with Photis or the many women before her who do not appear in the book? Perhaps fortune turned him into an ass in order to better embody his true character?

Charite’s story comes to a tragic end – an end quite unlike the tragedies of Lucretia and Philomela. A man who lusts after Charite and slyly ingratiates himself into her family kills Charite’s husband. When her husband appears to her in a dream and tells her the truth of his death, she exacts a violent revenge: “So she prophesied; then, taking a hairpin from her head, she plunged it deep into both eyes, leaving him totally blinded” (135). In exacting her revenge, the reader is not horrified by her behavior, as one may be of Medea, but is instead elated by her success. How the tables have turned! Suddenly, the women are calling the shots.

But Apuleius does not waste too much time on the righteous young woman and goes on to tell a story about a poor man with a wife “notorious for her outrageously immoral behavior “ (149). The wife was engaged in extramarital affairs when her husband came home early. The cunning wife devised a plan to deceive her husband, who never suspected her treachery. While the reader is meant to sorry for the poor husband, one cannot help but be in awe of the brilliant trickery of the wife. Following this story is another one about a woman who successfully cheats on her husband, with help from a fickle slave, Myrmex, who “was haunted by the fiery vision of that gleaming gold” (157). Again, Apuleius has turned things around. Men typically talk about women’s unruly desire for gold, diamonds, jewelry, and all material things, yet here Apuleius presents his readers with a man who loses himself to the allure of gold.

When Apuleius is sold to a miller he encounters another “evil” woman, the miller’s wife. I say “evil” because one must remember that we are looking at these women through the eyes of a man. Whomever a man has deemed evil may not be so, although it is hard to find redeeming qualities in the miller’s wife. She does, after all, cheat on him with a much younger and somewhat reluctant boy, gets caught, and conjures up a ghost to kill her husband in retaliation for him divorcing her. But her story is far less depraved than the one Lucius tells of a “wicked” stepmother who falls in love with her stepson. The story echoes that of Phaedra’s, who appeared first in Euripides’ Hippolytus, and later in Seneca the Younger’s Phaedra. The story is about a woman who is lovesick for her stepson. When he refuses her advances, she frames him with the death of her biological son. Though the case goes to trial, the woman is eventually undone by her own wrongdoings. Apuleius seems to be unable to decide whether the women of his story should be punished for their crimes or allowed to roam free in comedic recompense.

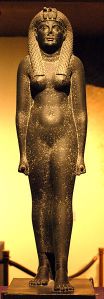

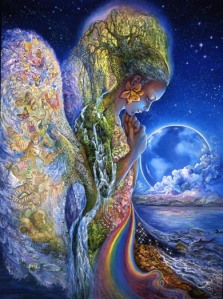

The final female who appears in The Golden Ass is perhaps the most significant. As Lucius is on the seashore he appeals not to the gods, but the goddesses of his realm. The goddess who appears to him is Isis, “Mother of the universe, mistress of all the elements, first-born of the ages, highest of the gods, queen of the shades, first of those who dwell in heaven, representing in one shape all gods and goddesses” (197). Isis is an Ancient Egyptian goddess whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. She was worshipped as the ideal mother and wife as well as the patroness of nature and magic. She was a representation of the pharaoh’s power, as the pharaoh was depicted as her child. In a reversal of Hesiod’s Theogony, she was born of Geb, god of Earth, and Nut, goddess of Sky. She is Lucius’ savior and appears the almightiest of the mighty, a female at the head of the totem pole.

What does Apuleius’ host of adulterers, goddesses, witches, young virgins, old hags, and obstinate maidens say about women in antiquity? Not much. His story is unique because of the abundance of female voices present – a breath of fresh air from the usual mute maidens of Vergil, Livy, and others. But it is still not clear on which side of the gender scale he slides towards. It is even less clear what the women of his time more likely embodied. As we search for women in the gaps and silences of history, we are able to piece together more of their lives, but what does the ever-present voice of women in Apuleius’ The Golden Ass tell us about women today?

It tells us that gender binaries are very much present and these typical female personas constructed by men still permeate society. All one must do is turn their skeptical glance to the film and television industry. Look at Disney. Almost 90% of the time, the villain is a female – a maniacal witch jealous of the beauty of the princess. Sounds familiar? The princess does not do much but look pretty and await the arrival of her prince to thwart her impending death. Where are the strong female leads? They often take the shape of coldhearted, bitchy businesswoman or generally unpleasant individuals who need to “lighten up.” When a woman takes control she is condemned for it, when a man takes control he is praised for it. As we fully embrace our post-modernity, I believe we are seeing rapid changes to technology and our social structure. Women are finally beginning to level the playing field. But is it enough? Will it ever be enough? Can we truly make ourselves heard while men still pull the strings, produce the movies, write the novels, and run the country? When do we finally get to write our own past, present, and future? When we write it, what will it be? What is the voice that will emerge from a group of people who has long been thought of as “Other”?

Just the other day I was with a few friends and one of the boys in the group remarked, “It seems like things are really getting better for women. I mean aren’t we all almost equal now?” This sparked a protracted response from me about how things are getting better, but we still have a long way to go. Somehow the conversation turned to whether a female president would be the next thing in store for America. “But that will never work,” another guy said, “Women are way too emotional. The country will fall to pieces.” “Yes,” I thought, “We still have a long way to go.”